(Originally published on Substack.)

In 2014, I published a chapter on contemporary muckraking fiction in the edited collection, Blast, Corrupt, Dismantle, Erase: Contemporary North American Dystopian Literature. The chapter is on fiction by Chris Bachelder and Robert Newman.

The essay’s driving question: in an era that has spawned numerous dystopian novels—an era apparently so in need of dystopian critique—why haven’t more straightforwardly realist or muckraking novels seen daylight? After all, there’s a rich tradition of political writing in this genre in the United States and elsewhere.

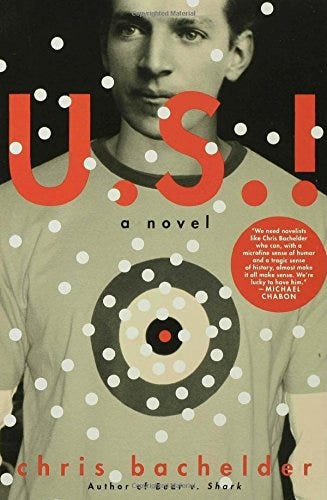

As part of my research, I emailed Chris to ask him about his second novel, U.S.! Songs and Stories (2006), and about the plight of the contemporary political novel. U.S.! is about Upton Sinclair, resurrected by an ailing left to write new up-to-the-minute muckraking novels.

It’s hilarious—but, I think, still sadly out of print.

Chris is the author three other books, including Bear vs. Shark, Abbot Awaits, and The Throwback Special.

The interview is great. After I saw how good it turned out, I intended to pitch this interview to the Los Angeles Review of Books, but through some accident of history the interview was never published.

Still, I think it’s as relevant as ever, so I present it here, lightly edited, with Chris’s permission.

LK: How did you think about the metafictional or postmodern (or whatever) form of your book in relationship to the kind of writing that Upton Sinclair was doing. It seems notable that your book isn’t a 600 page muckraking novel. Why not?

CB: The answer to a question like this is in part always, “Because this is what I do.” In other words, a writer’s formal choices have a lot to do with the writer’s personal and idiosyncratic tendencies, preferences, skills, and shortcomings. I’m drawn to collage, I’m excited by formal invention, and I tend to lose conviction when I go into a more traditional realist mode. That said, however, I think there are good conceptual/political/literary reasons to approach this particular book this way, and if there weren’t, I wouldn’t have gotten very far with it.

I wanted, quite explicitly, to update the political novel. If I wrote an earnest 600-page muckraking novel, I would be, literarily speaking, facing backward. U.S.! is not just a political novel, but a novel about the very possibility of political novels in our age, and it seems to me that the form should be hyper-contemporary, that the form should take into account the conditions of our time. One way to demonstrate how absurdly out of step Sinclair seems a century after The Jungle is to set him down in our time, and to set him down in a wild scrapbook of a novel. The form creates a lot of noise, a lot of strange cuts and transitions. This creates nice friction with Sinclair’s earnest and righteous crusading. The book admits that his kind of muckraking isn’t valid anymore—you can’t write that book. But if the book says you can’t write a political novel, it also seems to say, you can’t not write a political novel. The world, after all, is crumbling. Novelists must have something to say about this. But a novel that is straightforwardly about the crumbling world is no longer considered art. What are you supposed to do? How to proceed? The engine of the novel is, in a sense, profound ambivalence. The book did not take on life until I found a way to write from a kind of anguish or questioning. To me the tone is different, more complex, than in Bear v. Shark.

Another point, very pragmatic, is that the form allowed me to resurrect Sinclair off stage. I could just assume his many lives. The gaps between chapters in a sense do this work. I would not have to dramatize multiple deaths and resurrections. I did not want to have to address this question of resurrection directly. I wanted readers to just take it as a basic rule of this world. We don’t ask why Gregor has turned into a cockroach. Kafka doesn’t want us asking that question.

Not until I finished the book did I start to see the ways in which the form is itself political. I wanted the opening section of the book, the scrapbook, to feel proliferative, energetic, and, well, revolutionary. Each new chapter is a resurrection, a new start. I wanted a sense of wild possibility, not limited by conventions of plot. Even when the subject matter of these sections is dark, the feel of the book is, I hope, is expansive, invigorating. I wanted a kind of revolutionary spirit here. Then we come to the novella, the bookburning section. Here I used very conventional plotting. It’s a convergence narrative, all the characters coming together, with tragic results. I see a kind of funneling toward Greenville. So if the early section opened up, this later plot-driven section closes down. Mark Edmundson in a book called Why Read? says that form is feeling, form is the way authors infuse their work with emotion. This opening and shutting is my sense of the feeling of U.S.! And when I finished, I saw that there is a way in which the novel implicates realism, that it associates realist form and plot convention with the (near) eradication of the revolutionary spirit. Realism in a sense shuts the book down, narrows its possibilities. I don’t offer that as a generalized theory or critique, and I certainly wasn’t working with that idea, but I’m interested in how it worked out in this particular book.

And I say all this while realizing that this novella is perhaps more satisfying and substantial than collage, that it gives readers something they crave, and that it almost certainly generates stronger feelings than my earlier bag of tricks. There’s also the very practical point that the early stunts provide the reader with the necessary background for the novella.

LK: I am framing the chapter I’m writing on contemporary muckraking fiction with a Jonathan Franzen interview, where he says the following:

JF: Well, I’m a fiction writer. I’m political only as a citizen, not as a novelist. I do what I can as a citizen, and also, in a small way, as a published writer helping to raise money. But once you start asking your question as a novelist, your art’s in danger of becoming illustrative or didactic—in some sense, an act of bad faith. The contract with the reader is that you’re both in the adventure together, that there’s no bait and switch going on, no instruction masquerading as entertainment.

“Not that there can’t be legitimate political and social by-products to good fiction. It’s hard not to read Lolita and have a little sympathy for child molesters. If you like that book, you might rethink the most draconian criminal punishments for child molesters. You might have a little more compassion in general. That’s the way fiction is supposed to work. It’s a liberal project. When Jane Smiley uses the phrase “the liberal novel,” she basically means “the novel, period.” The form is well suited to expanding sympathy, to seeing both sides. Good novels have a lot of the same attributes as good liberal politics. But I’m not sure it goes much further than liberalism. Once you go over into the radical, a line has been crossed, and the writer begins to serve a different master.”

How do you respond to Franzen’s description of the novel’s politics? U.S.! would seem to deny the claim that radical novels “cross a line” that shouldn’t be crossed. You seem to have rejected your postmodern early fiction in precisely the opposite way that Franzen does—by hoping to find a way to insert more politics into the tradition, not to remove politics from it.

CB: Franzen’s view is the orthodox view at this cultural moment, but we should remember that The Jungle was regarded as a literarily successful novel upon its publication—I wrote about its publishing history, and the shifting notions of the novel, in an essay for Mother Jones a few years ago. My point was that a good novel had somehow become bad. The words on the page are of course the same, but what has shifted is our notion of what a novel is and what it does. Now, Franzen’s position is regarded as non-controversial, hardly worth saying because it is assumed to be true.

The blind spot of classical liberalism is that it does not see itself as a position. It sees itself as a procedural mechanism, not a substantive agenda. It’s a marketplace, a clearinghouse, a space where competing ideas can gather, and the idea is that the best position, whatever that might mean, will win out. Liberalism wants to be a container for all positions, not a position itself. When it gets challenged from the right (fundamentalism) or the left (so-called radicalism), it is revealed as a position. It becomes visible. You might say it is actually a form of fundamentalism because its procedure cannot be challenged. When other systems cannot fit into its procedural space, it draws the line and says they are out of bounds.

(Franzen’s example of Lolita is strange and perhaps revealing. A book like Lolita could actually be used against Franzen’s argument. It seems to me that the power of the novel is not that you read it and say, “Oh, I see now that pedophiles are people too. I’m enlarged by this viewpoint.” That book might exist, but it’s not Lolita. The power of the novel is a kind of second-order shock that you’re being charmed by an unrepentant and shrewd sexual predator who happens to be a brilliant and charismatic prose stylist. So there’s a way in which the book is assuming and exploiting liberalism for its effect. It’s a case study in the limits of liberalism. It’s what happens when you extol the virtues of the procedural (let’s hear from all the voices) over the substantive (sexual predation of young girls). So the book makes you say, Wow, I am really charmed by this Humbert Humbert, and I’m beginning to root for him, and there is a whiplash effect when you must say, “WAIT, what is happening? I’m rooting for a pedophile!” That can’t be right, and it’s not right, so to the extent to which it’s happening has to do with the seductive powers of the novel, its ability to arouse sympathy. I would say it’s precisely wrong to finish Lolita and claim that it complicates our ideas of pedophilia, that it complicates our notion of the criminal and the crime. The novel, it seems to me, is working cleverly against the liberal paradigm. If you let go of the substantive notion that pedophilia is a vile act, and you blandly celebrate the liberal novel’s ability to welcome all viewpoints, you’ve missed the point exactly. So you could see the book as a critique of liberalism’s blind spots. Humber Humbert has a point of view. That point of view is terrifyingly wrong and bad. If we read the book to honor his point of view, we may be getting it wrong. The novel is interesting because it creates discomfort—we know Humbert’s point of view is vile and yet he is charismatic and his obsession is compelling. If you choose to celebrate the nuanced voice of a sexual predator in terms of empathy or openness or tolerance, then you’ve fallen into the book’s trap. The only way to step out of the trap is to step out of liberalism, which is extraordinarily difficult.)

I go into all of this only to draw an analogy between classical liberalism and contemporary views of the novel. There are interesting parallels. People talk about these things in the same way. The novel fits well into the liberal ideology—it’s a space where competing views can be dramatized. The author does not (should not—this is ethical) have an agenda. She does not advance a position. Pedophilia is not so much wrong as it is complicated! Let’s see this from all the angles. I’m interested in Chekhov with regard to our contemporary notions of art. He was among the first to say that the author should not have a point of view. He valued ambiguity, complexity, mystery. This is our notion of high literary art, while Sinclair’s notion has declined. It’s barely art.

But of course not having an agenda is an agenda. Not having a point of view is a point of view. This is the parallel to liberalism. I’m trying to write about this now in some essays. Chekhov, widely celebrated for not having a program, advances his non-program with the fervor of a crusader. He’s a strangely programmatic writer, that is. He devastates his characters, strips them of faith and resources, reduces them time and again to anguish and bewilderment.

Franzen et al obviously value empathy, sympathy, compassion. What else? Complexity, mystery, wonder, ambiguity and so on. These are programmatic, self-evident goods. They are not up for negotiation within the liberal marketplace. Liberalism has its values, and just assumes them, instead of arguing for them, instead of making them part of a substantive case of goods. And so what would a liberal novelist say about a novel that seems to be cruel, avaricious, selfish, and certain? That poses a challenge to core values, and so it’s not allowed. They say it’s not allowed on procedural grounds—that is, it doesn’t dramatize competing points of view in a complex way—but it’s just as true to say that it’s not allowed on substantive grounds (i.e. its values are bad, they don’t contribute to human flourishing).

This is a very, very tricky topic. (This is the liberal in me talking!) The truth is, Franzen et al are no doubt correct that advocacy can destroy art. When I feel that the author is trying to persuade me, when I feel that the drama is predetermined, that the characters exist only to advance some political point, I of course am turned off. When I read Franzen’s comments, I don’t recoil violently; I’m just made slightly uncomfortable. I love Chekhov. I liked The Corrections. I no doubt celebrate, in my writing and teaching, mystery, wonder, complexity, etc. But I do have a sense is that the novel can and should do more, that it can be more engaged.

For me it’s a question of foreground and background concerns. The novelist doesn’t have to throw up his hands and say, “Who’s to say whether global capitalism is bad?” The novelist doesn’t have to make every issue complicated. The novel has values, and it can have strong values. Its background can be composed of strongly held beliefs. U.S.!, I think, takes for granted some basic positions and values about economic fairness. But the novel was flat and dead until I found a way to complicate matters in the foreground. I just had this infirm martyr figure, limping around, acting righteously, and getting killed. He was merely a victim, and the book was going nowhere. Then I started reading more on Sinclair, and what happened is that my views on him as a person got way more complicated. I admired him and I found him terribly annoying. And that’s when the book took off, that’s when it had life. I was able to write from a position of ambivalence. I was able to write from a question (as Chekhov instructs). The question is, How in the world are you supposed to create political art? Maybe I succumbed to my own profound liberalism, but that was the way for me to get the book written. I wanted desperately to write a political novel, but I couldn’t figure out how to do it. But the important thing is that the book is not ambivalent about inequality, not ambivalent about our economic system. Those are firmly held and substantive background values.

George Saunders is interesting in regard to this topic. This is from a recent interview:

Q: The story seems to come down quite strongly against the notion of suicide in terminal patients. Is that your own view?

A: Oh no, not at all. Or—I’m not really sure how I feel about that issue, honestly. I think the story comes down strongly against Eber’s suicide, on this particular day, by this particular method, if you see what I mean. I think fiction isn’t so good at being for or against things in general—the rhetorical argument a short story can make is only actualized by the accretion of particular details, and the specificity of these details renders whatever conclusions the story reaches invalid for wider application.

I think this is beautifully articulated. I find myself nodding when I read it. And yet in the background of Saunders’s fiction we see many clearly held values, if not positions. What he does is extends out to the edge of something where, perhaps, he’s unsure. And that’s where his fiction can operate. But if you look at the unquestioned, unmysterious base of the fiction, you see strong political sentiment.

I don’t know….I’ll be thinking about this my whole career. But at this point I’m not ready to say, “OK, there’s me as a writer, and then there’s me as a citizen, and these two have to be kept distinct.” It doesn’t make sense to me that a novelist would say that he can’t extend his deeply held personal values into his art. Certainly there must be ways of extending our rich tradition of so-called political fiction. Ways that take into account our contemporary notions of art. This is a thorny issue—but the answer, it seems to me, is not to give up on deeply engaged fiction, but to find ways to do it in a nuanced and sophisticated way.

LK: What challenges, if any, did you face in getting U.S.! published? The book is currently out of print. Are there any plans to reissue it?

CB: I had much more trouble publishing my new domestic novel than U.S.! I had a relationship with an editor at Bloomsbury, and she took it. We didn’t send it around, so I didn’t get a sense of its reception in NY publishing. There are no plans to reissue that I know of.

LK: What is the relationship between your most recent novel, Abbot Awaits, and U.S.!? It seems quite different—and leads me to wonder how you regard U.S.! today, five years after its publication?

CB: Abbott Awaits is a very quiet domestic novel about marriage and fatherhood. It grows directly out of a specific time in my life. It’s much different in many ways from my previous satires, but if you’re looking for continuity and similarity, you can certainly find them. In some ways all of my work has been about trying to find a place to stand, a way to be in the world. The new novel is not apolitical, but it’s certainly not overtly political. The book doesn’t signal a shift in my thinking, or some kind of retreat—it just comes out of my life. I got married and had two kids, and for a time there I simply couldn’t invent worlds, couldn’t work with a big canvas.

I’m proud of U.S.! and of Abbott Awaits. There are some gags in U.S.! that I might regret, but in general I have a great fondness for the book, its premise, its form, and especially its tone. I emptied my cup on that one. I wrote the political book I felt I needed to write, and I found a way to make my satire more emotionally rich. The cup has to fill back up, and it will. And hopefully I’ll discover (or steal) some new ways to do what I want to do.

LK: I disdain the recent tendency to see the contemporary literary world in terms of the Franzen-DFW friendship/psychodrama, but let me hypocritically do just that for a moment. It seems as if your writing is very much in Wallace’s corner, so to speak. Your Believer essay on Upton Sinclair seems to me to be similar to Wallace’s “E Unibus Pluram,” in as much as your essay announces a kind of break in your writing. You seem to think that Bear vs. Shark fails, whether aesthetically or politically, it’s not clear to me, and that you wanted to move beyond irony and satire with your post-B vs. S work. Is that a fair characterization? And yet one of the ways you differ from Wallace is in imagining that the move away from irony must, to some degree, be a move toward politics or (here you quote E. L. Doctorow) a “poetics of engagement.” How do you feel about these arguments today? Are there other writers out there who are involved in imagining such a poetics?

CB: A move away from the prevailing and totalizing irony of the day is a move toward engagement. It’s a necessary first step. I don’t see a lot of writers working toward politically engaged fiction, but I see a lot of writers wrestling with issues of irony and authenticity. I just read and enjoyed Ben Lerner’s novel Leaving Atocha Station, which is a book about trying to be a real person, trying to find a place to stand. I think these are the books that younger writers have to write as we try to come to terms with a thoroughly ironic worldview that turned out to be an aesthetic cul de sac. So what I see are books that are turning around, trying to head back. And tone is the new plot. Tone is the engine and the challenge, the issue that writers must solve. What is my emotional stance toward other people and toward the world?

You characterized my previous position fairly. I felt stuck in the cul de sac. What’s changed for me perhaps is my notion of engagement. Lydia Davis has a chapbook called Cows. The whole thing is composed of observations and speculations about three cows that live across the street. This project is not overtly political, but it is deeply, deeply engaged. And to the extent that it is truly attentive—and that its attentiveness implicitly confers value on the object of observation—then maybe the work is political. That argument—that everything is political—used to drive me nuts because it ignores important distinctions and it halts discussion, but there is a way in which just closely paying attention (to anything) has become a kind of radical methodology.

Wallace was in some respects driven by tonal tensions. He was phobic about, on one hand, sentimentality and moralism, but on the other hand, glibness and detachment, and his extraordinary style is the product of those fears. Or to put it more positively, his style was his quest for engagement, wakefulness. I’m sure he would have shuddered at the term “political novel,” but it seems to me he was driven by the urge to engage meaningfully and authentically. Which is not to say directly, of course, as is clear from the shapes of his fiction and the shapes of his sentences. It wasn’t easy to avoid everything he wanted to avoid. As Donald Barthelme wrote, “Art is not difficult because it wishes to be difficult, but because it wishes to be art. However much the writer might long to be, in his work, simple, honest, and straightforward, these virtues are no longer available to him.” In one respect, Wallace proved a great model for many of us as we tried to become more engaged and to break out of habits of irony, but on the other hand, because he is such an attractive stylist many of us ended up imitating him, which of course reflects an engagement with Wallace, not with the world.

LK: Occupy Wall Street has recently drawn critical attention to income inequality, student debt, and the pernicious effects of capitalism. I wonder if you see the need for an artistic dimension to these political and organizational efforts. One of the things that motivated me to write about your novel in the first place was the relative paucity of political novels in an era that seems aching for more political art and culture. We are living through what many commentators, economists, and political scientists describe as a New Gilded Age. Is there any hope for a New Progressive Era among artists, journalists, and creative professionals? How might a poetics of engagement work in the present? Are partisanship and artistic integrity irreconcilable?

CB: Like you, I would expect that we would see a resurgence of political art. A hundred years ago there were many novels that clearly grew out of authors’ basic sense of unfairness. (Many of these writers started out as journalists.) That voice in the back of my head says I must find ways to address inequality, greed, stupidity. Let’s face it, things are very, very bad, and it seems to me that art has to respond in some way. But Roosevelt read The Jungle and invited Sinclair to the White House. They corresponded by letter and telegram. That’s nearly impossible to imagine today. The novel is not culturally important, and almost nobody is naïve enough to think it can change the world. So if you’re terrified and angry and sad about the state of the world, it’s a strange thing to go sit in your room for a few years and write a novel about it. The Occupy era already has some great art. The posters, for example, are amazing. And there is music and good journalism and video. This will all continue, with or without the novel. Partisan art is not a contradiction in terms. I just think the artist must find a way to surprise herself, to wade off into uncertainty and ambivalence, where the art can be angular and alive.